by Roy Curry

“Fan–Bloody–tastic!” The voice emerged from under a heavy-duty hoodie.

I was close to a figure standing alone. He was leaning into the wind on the exposed passenger deck of the large car and passenger ferry that ran between Newcastle in the UK to Bergen Norway.

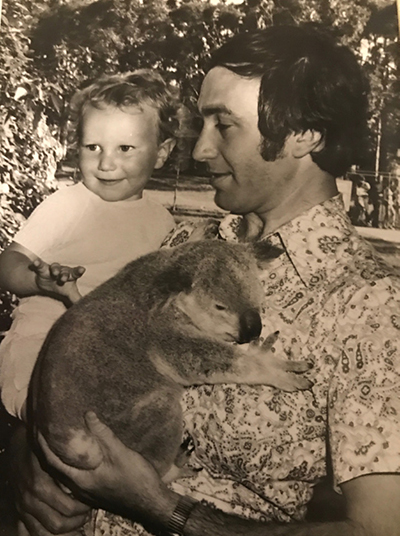

I caught the “Fannnn…stic” again as the wind eased slightly, the all-purpose Australian adjective. He had to be another Aussie: just the two of us struggling to maintain our footing as the ferry heaved in the rough North Sea. There was no one else on deck on that early June morning, 1973. Sue and 18-month old Andrew strategically remained horizonal in a tiny cabin far below deck.

We were travelling north parallel to the Norwegian coast. At times an off-shore rocky island protected us from the North Sea. Then settlements, not big enough to be a village, appeared clinging to land where mountains did not drop directly into the sea.

As the ferry pitched and rolled there was more than just this deck that was shaping how well my feet were firmly on any ground.

“Far from home?” I asked

“Yeah, Sydney. Stone’s throw from Bondi Beach. You?

“Brisbane, but living in the UK.”

Were we really true-blue Aussies? Who were we?

“Been to London, bought our VW van there, couldn’t wait to leave. I wouldn’t live in England. There’s no place like Oz.”

I’d heard those words before. “There’s no place like Oz”(Australia), followed by “Best country in the world.”

I wanted to believe this, but not in this no-holds-barred sort of way.

Australia had elected a popular center-left prime minister the year before. He had withdrawn the country from the Viet Nam war on the night of the election, thrown off some of the old British Empire’s shackles, funded the Australian movie industry (hence Crocodile Dundee) and added a zing to the well stablished tradition for young Australians to travel far and wide across the globe before being officially declared adults.

Sue and I believed we were doing our own version of this adventure, albeit with a toddler in tow. But something was changing in us.

New vistas were opening before us. We could live in Oxford for two more years, my research was entering a new area and was not ready to be moved to a new lab 10,000 miles away. Sue was beginning to explore career options that would not involve teaching high school French.

Were we really true-blue Aussies? Who were we? When we took a holiday back to Australia from the UK to visit family, the Qantas audio system played “I Call Australia Home” as our plane parked at the gate of Sydney. Little Andrew asked, “Why’s Daddy crying?”

But not too many days after the initial excitement of arrival, that same little voice asked, “Will I see my friend Daniel soon? I want to go home. “ Where was home? Could we have two homes?

Several weeks later, as I watched Bondi Beach disappearing below from the plane window a hook somehow began to reel me back along a line that landed firmly with friends and colleagues in Oxford. We were learning a new state of mind: to be displaced, yet comfortable in that displacement, energized by the tension. It was to serve us well.

One of those colleagues in Oxford was an American on sabbatical, Dr Gene Renkin. He visited the lab for several months from Duke University and had played a key role helping me design my research project. More than two years later when it was finally time for us to leave Oxford, he invited me to spend time in Davis where he had recently moved as the new Chair of Physiology. We spent the summer of 1975 in Davis. We lived in an apartment on I Street in downtown, right beside the train tracks. At that time the north bound Coastal Starlight rumbled right through our apartment at 2:00 a.m. each morning.

It was easy to love Davis, in many ways so much like parts of Australia.

That stopover delayed our return to Australia. It also set in motion the second stage of our displacement saga. In 1977 we departed Australia for a second time, this time to live (away from the train line) and work in Davis California. US Immigration dictated that our visa was valid for just five years. A green card and dual citizenship were still in the future.

It was easy to love Davis, in many ways so much like parts of Australia. Eucalypts and acacias (wattles) grew on campus, and a short drive took us to the open flat landscape that Sue knew from the Mallee region of Victoria, plus my teaching and research were all I had hoped for. Sue began a business of importing Australian books and selling them by mail. Soccer games, school, and bikes kept our children happy.

Were we now settling? Less displaced? Not really.

These days United Airline’s Dreamliner does not play “l Call Australia Home” as we approach the gate in Sydney, but the old farm house near Brisbane still stands with all the memories of childhood years. But race horses have replaced the dairy cows. My sister always has cocker spaniels in her home, one looking remarkably like Blondie, the dog we shared as children. On the flight from LA to Sydney I need time to adjust, pushing Davis, California and the US a bit further back in my mind and letting the Australian in me be set free. And it is made easier because Australia has changed. The first announcements as we enter Customs and Immigration at the airport include Mandarin, Hindi, and Tagalog. Our Aussie friends no longer ask when we are coming home. Instead they tell us,

“Our son’s wife is from Virginia, they live there now, and we are off to visit them and our grandkids next month. We love being in the US. And when, as a tourist myself traveling with a group of Australians in the Kimberley in Northern Australia, we spy an unusual plant growing wild, some of the Australian in me re-emerges.

“I know that plant from my childhood. It’s a rosella bush. My mother grew these in our vegetable garden on the farm. The calyx of the flowers is used to make a special jam. It’s bloody fantastic.”