by Kathleen Stack

“How do you know we are not being kidnapped?” Mom cried out. My command of the Moore language was not very good, but I sensed from the few words I understood and the look on the faces of the men who had intercepted us, there was some kind of emergency. I veered off the dirt road into the bush, following their moped.

Mom and my younger sister, Anne, had come to visit me in Boulsa, Upper Volta (now Burkina Faso), a sleepy town of 6,000 people. It was 1979. I had secured a good, paid internship there with Foster Parents Plan as the Assistant Country Director. I was taking Mom and Anne back to Ouagadougou, the capital, for their flight home. For a week or so, they had shared my four-room, whitewashed cement “villa” with me, taking bucket baths, using my outhouse and chatting by kerosene lamp in the evenings. They joined me on day trips to villages to open schools, discuss the location of new wells with village chiefs and supervise baby weighing and health counseling.

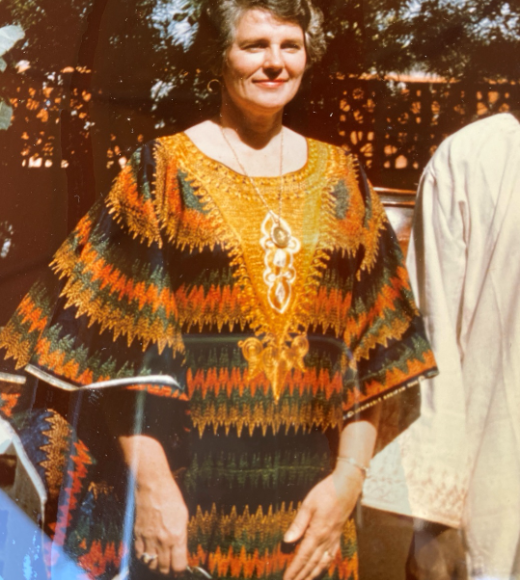

Mom, at age 53, was a trouper. She endured the heat and hardship with a wonderful sense of humor and deep enjoyment of the adventure. I gave my dad a photo of her entering the outhouse, holding up a roll of toilet paper and her Tucks hygienic wipes, with a big smile on her face.

But Mom was not happy with this detour into the African bush. I was driving the office Peugeot pick-up truck. The men led us on a narrow bike path through brush and trees. I cringed at the sound of branches scraping the truck body as I tried to keep up with them. Mom’s fear contributed to the tension. She wasn’t used to following strangers into the woods.

It was hard to disobey. She was my mother after all. But I knew this place better than she ever would, so I kept on driving.

“Why are you doing this, Kathy? You don’t know these men. They could be dangerous! You should turn around.”

I wasn’t sure what we were getting into, either, but I’d lived in this part of the world for four years. I traveled regularly around the Boulsa region to remote communities, although always with a driver and staff. I tried to reassure her. “Mom, it will be okay.”

She continued to plead ‘What if they try to kill us? What if they steal our bags and money?” It was hard to disobey. She was my mother after all. But I knew this place better than she ever would, so I kept on driving. Anne remained silent, not knowing what to think.

After a harrowing twenty-minute drive, which felt like an hour, we arrived at a small, round mud hut with a thatched roof. Chickens clucked and scattered as we pulled into the courtyard. The two men rushed into the hut.

Poverty defined this place. Women, children and an old man, all in torn, oily clothes, gathered around our vehicle, their dusty faces peering at us. The kids had runny noses and flies were abundant. Blackened cauldrons lay on their sides. A large wooden mortar and pestle for grinding millet rested unused.

There wasn’t much time to take it all in, though. The men rushed out of the hut holding a convulsing woman on a straw pallet, which they quickly slid into the open bed of the pickup. Her body jerked upward with spasms. About six men leapt onto the back of the truck. Now I was afraid. I asked Anne, who was a newly-minted prenatal intensive care nurse, “What do you think? Can you do anything?” She went back to look and instructed the men to turn the woman on her side to prevent her choking on her tongue. She returned to the cab pale and looked at me, feeling helpless without any tools of modern medicine.

I spun my wheels making a K-turn to return through the bush to the road leading to Pouytenga, about an hour away, where I knew there was a health clinic. Mom was upset and began crying. Then she became angry. “Why is this happening? Why is there no doctor nearby?” As I drove, my attention was divided between helping my mother understand the weak health care infrastructure in Upper Volta and not crashing into a tree.

I was relieved to get back to the main road, dusty and potholed as it was. I knew this road well and safely navigated its deep ruts and a partly washed-out bridge. An hour later we arrived at the health center. Uniformed health workers ran out and, together with our passengers, took the woman off the truck and into the building. I worried, knowing how crudely equipped these places were, but there was nothing more we could do than to wish them good luck.

Mom and Anne flew out the next day to Paris to connect with their flight back to New York. I stayed in Ouagadougou for a few days, working at headquarters. On my return trip to Boulsa, I stopped at the health center to inquire about the woman. I didn’t know her name, but the staff instantly connected their patient to the nasara, the local name for a white woman, who had dropped her off.

“She recovered. Her family took her home.” the health worker told me. “She gave birth a few weeks before you came. It was tetanus.”

I sighed with relief and offered many thanks. As I drove back to Boulsa, I thought about how this near-tragedy could have been avoided with Tetanus Toxoid vaccine. I promised myself to do more to educate pregnant women.

Mom was greatly relieved to learn that the woman had survived. She said she was proud of me for persisting and then added that she admired my expert driving over terrible terrain. I smiled to myself and thought about how truly independent I had become.